The term Batak designates any one of several groups inhabiting the interior of Sumatera Utara Province south of Aceh: Angkola, Karo, Mandailing, Pakpak, Simelungen, Toba, and others. The Batak number around 3 million. Culturally, they lack the complex etiquette and social hierarchy of the Hinduized peoples of Indonesia.

Indeed, they seem to bear closer resemblance to the highland swidden cultivators of Southeast Asia, even though some also practice padi farming.

Unlike the Balinese, who have several different traditional group affiliations at once, or Javanese peasants affiliated with their village or neighborhood, the Batak orient themselves traditionally to the marga, a patrilineal descent group. This group owns land and does not permit marriage within it. Traditionally, each marga is a wife-giving and wife-taking unit. Whereas a young man takes a wife from his mother’s clan, a young woman marries into a clan where her paternal aunts live.

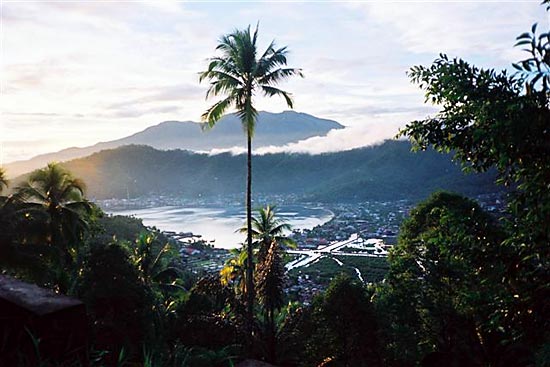

When Sumatra was still a vast, underpopulated island with seemingly unlimited supplies of forest, this convergence of land ownership and lineage authority functioned well. New descent groups simply split off from the old groups when they wished to farm new land, claiming the virgin territory for the lineage. If the lineage prospered in its new territory, other families would be invited to settle there and form marriage alliances with the pioneer settlers, who retained ultimate jurisdiction over the territory. Genealogies going back dozens of generations were carefully maintained in oral histories recited at funerals. Stewardship over the land entailed spiritual obligations to the lineage ancestors and required that other in-migrating groups respect this.

The marga has proved to be a flexible social unit in contemporary Indonesian society. Batak who resettle in urban areas, such as Medan and Jakarta, draw on marga affiliations for financial support and political alliances. While many of the corporate aspects of the marga have undergone major changes, Batak migrants to other areas of Indonesia retain pride in their ethnic identity. Batak have shown themselves to be creative in drawing on modern media to codify and express their “traditional” adat. Anthropologist Susan Rodgers has shown how taped cassette dramas similar to soap operas circulate widely in the Batak region to dramatize the moral and cultural dilemmas of one’s kinship obligations in a rapidly changing world. In addition, Batak have been prodigious producers of written handbooks designed to show young, urbanized, and secular lineage members how to navigate the complexities of their marriage and funeral customs

.